BIOT Science Expedition 2014 - Pouring tropical rain - Day 4

Pouring tropical rain

Today rain poured from the sky. Not the half hearted wettening that many of us are familiar with in Europe but rather the humid heart of the tropics poured out in a torrent from the heavens. We may have got more than a little damp during the days activities. When we awoke the curtain of rain was so dense that there was no prospect of diving or indeed any other excursion from the boat. Lucky for us the clouds were kind and parted for us to depart and get underwater.

Some headed out to conduct sea cucumber surveys, check autonomous reef monitoring systems or recover long term temperature loggers, while the remainder headed to the northernmost point of the atoll for an Oceanside dive. Hundreds of spinner dolphin greeted us as we motored out of the lagoon, careening along in formation around our bows and jumping in unison alongside us, almost within arms reach. It was a shame to break away from this mutual entertainment and stop to dive. But the sights underwater were just as delightful, if slightly less mobile. Once again beautiful vistas of corals with clouds of colourful fish festooned all around.

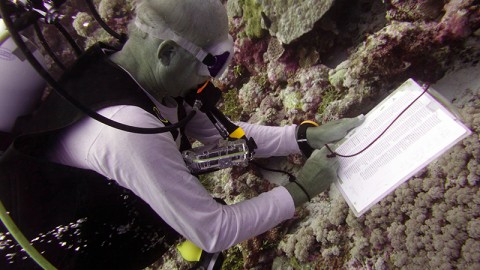

The god of tides and weather played funny again though and a roaring current picked up tearing at the divers trying to hold position over the reef. Getting back into the boat holding on for dear life with one hand while trying to unclip gear without it being swept away was a task and a half. The remaining dives for the day would be within the lagoon. A far calmer enterprise. I did see Doug hard at work before the current picked up and flicked off a few photographs of him doing his thing whilst randoming across the reef. He has written a few words to explain what he is getting up to out here in BIOT...

“I am studying the coral diversity and coral diseases of Chagos. Corals are particularly important on coral reefs, of course, because they are a primary builder of the reefs, and also because they provide habitat for many other species, particularly fish and small animals that live among coral branches. There are many fewer species of coral on most reefs than species of fishes, however, most individual coral species are harder to identify than fish. All studies of corals need to be able to identify the corals that are being studied, and corals are an important part of the biodiversity of coral reefs and the reef ecosystem. Many corals can be identified alive, underwater, but it takes lots of experience to learn to identify corals, learning to identify one species at a time. Further, different corals are present in different parts of the world, on different reefs, and in different zones of reefs, and even what we think are the same species can look different in different areas. The most secure identifications of corals are done with skeletons, because the actual taxonomy is based on the skeletons. So some collecting of samples of problematic or interesting species is helpful, and even collecting a sample to confirm identifications of all species strengthens a study.

In my study of coral species in Chagos, I take a slate with me on dives, with names of about 450 coral species on it, and check off the species as I find them. After each dive, I make estimates of the abundance of each species I found on a 1-5 scale. I like to survey from deep to shallow on a dive, since some species only live deep and others only live shallow. So looking both deep and shallow increases the number I can find. Further, I do a roving search dive, looking for more coral species. I start deep and work my way up into shallow water, since that is the safest way to do a dive. As I go, I photograph corals, trying to get a photograph of each species of coral in the expedition, and also trying to get photos of all the particularly interesting looking corals that I may not immediately be able to identify. Later I will work with various books to identify as many corals in photos as I can. I also will collect a few samples occasionally to use them to help me to try to work out what they are. I have this type of data from many dive sites from a variety of areas of the Indian and Pacific Oceans to compare my data with. This data compliments data from quadrats or video which gives more quantitative accuracy but usually doesn’t have corals identified to species and doesn’t find as many species.

Coral diseases are a threat to coral reefs. Diseases have killed the majority of two of the most common corals in the Caribbean, and more and more diseases are being found in the Caribbean. So far, diseases have been less of a problem in the Indo-Pacific and fewer diseases have been recognized in the Indo-Pacific. However, diseases may be on the increase in the Indo-Pacific and they aren’t studied nearly well enough to know. So I am photographing what appear to be diseases as I find them, and if the opportunity presents I am counting diseased colonies and healthy colonies as I survey coral species. My disease work will compliment that of Courtney, since she is primarily doing transects at one depth.”

So on completion of our sopping rainy day there is one last important thing to mention. Our number has been augmented. David Curnick, who has been doing shark research on board the research vessel provided by the Bertarelli Foundation, has crossdecked from that vessel to ours. Now that the Bertarelli Foundation's vessel has completed her research voyage she is departing but David is remaining with us to assist with coral reef data collection for the remainder of our trip. Welcome aboard...