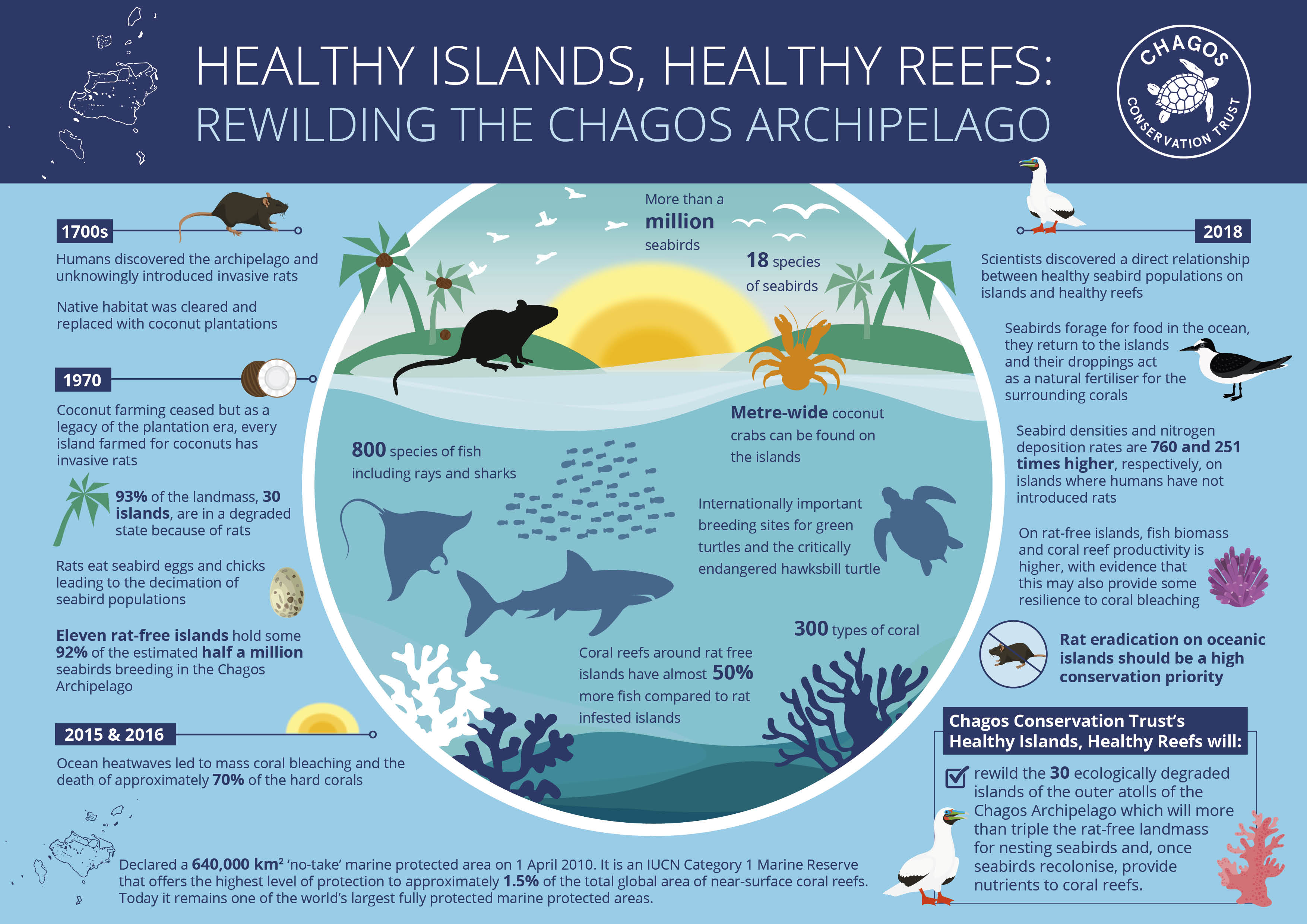

Rats, reefs and seabirds

In 2018 scientists from the Bertarelli Programme in Marine Science discovered a direct link between healthy island seabird populations and key reef health indicators, such as herbivorous fish populations.

Seabirds feed from the ocean and their droppings act as a natural fertiliser for corals that surround the islands they inhabit. Where rats are present, this relationship breaks down as rats decimate the seabird populations by eating eggs and chicks, and destroy native plants.

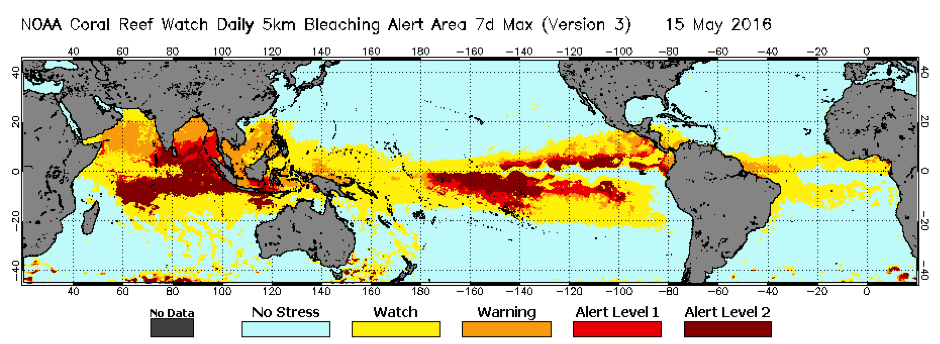

The researchers found that seabird densities and nitrogen deposition rates are 760 and 251 times higher, respectively, on islands where rats are not present. On the reefs around these rat-free islands, fish biomass and coral reef productivity is also higher, with evidence that this may provide some resilience to coral bleaching.

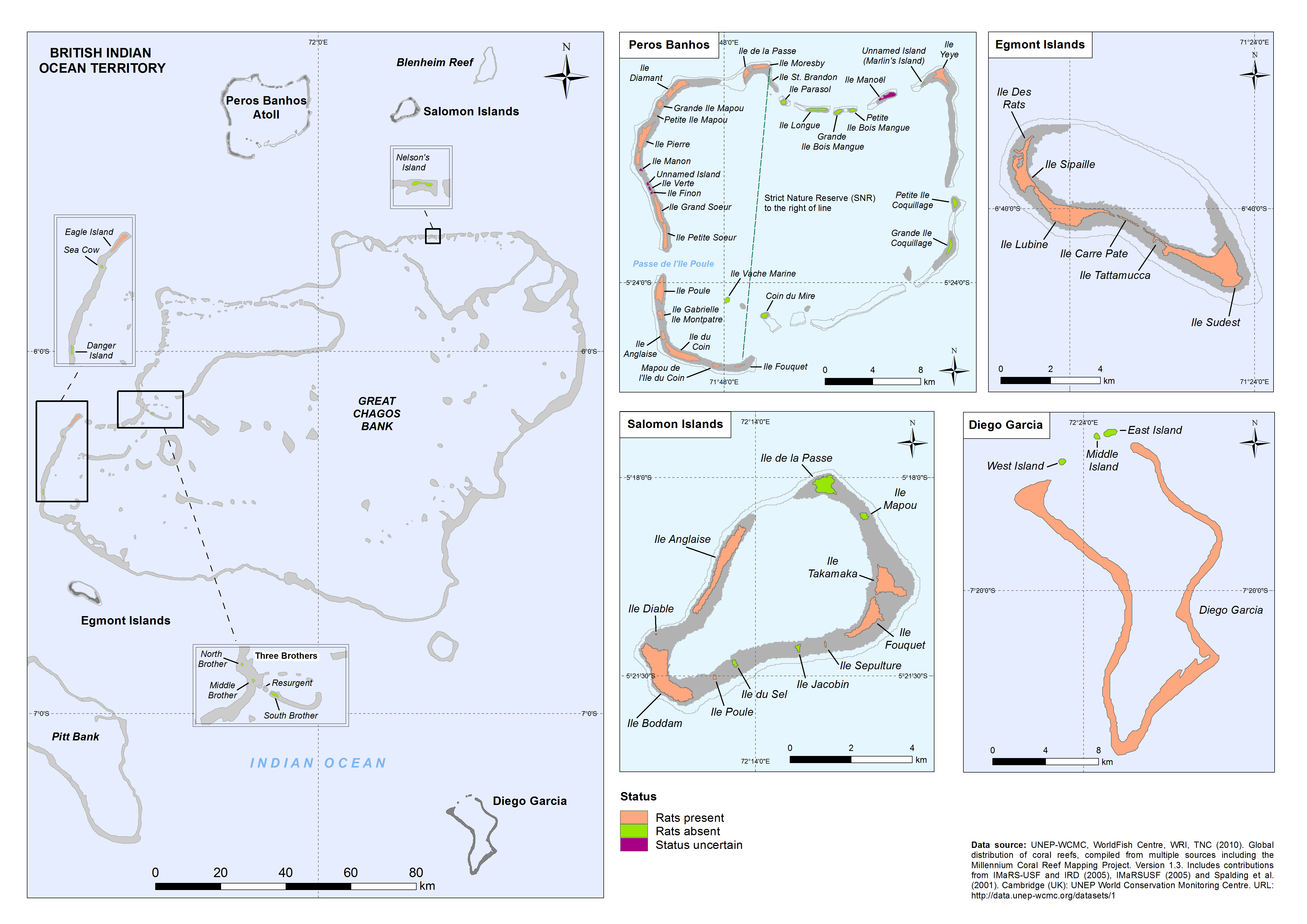

Currently, over 50% of the islands–constituting 93% of the landmass of the Chagos Archipelago–are in a degraded state resulting in a marked reduction of biodiversity and compromised coral reefs. The 30 rat-infested islands planned for rewilding have significantly fewer, to no, seabirds, particularly ground nesting species, to those without rats present.