A long journey to a conservation win: Restoring Ile Vache Marine

By Pete Carr, CCT trustee and island restoration specialist

By Pete Carr, CCT trustee and island restoration specialist

In 2014, after a five year gestation, we decided to try and eradicate ship rats, Rattus rattus, from an island in the Chagos Archipelago, of the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT).

Previously, in 2006, an attempt was made on the second largest island in the archipelago, the 245 hectare Eagle Island. In hindsight this was a near-preposterous adventure!

Rat eradications on tropical islands are still, globally, unsuccessful about 30% of the time. A decade ago to attempt to eradicate rats from such a large, remote and vegetatively inhospitable  island was the work of true gladiators. Sadly, despite some heroic endeavours, the attempt failed.

island was the work of true gladiators. Sadly, despite some heroic endeavours, the attempt failed.

Fast forward three years. With fear of another failure being the watchword, we at CCT decided to make an attempt.

Deliberately a small island was selected.

Deliberately, an island without any hidden secrets was selected, we did not want to discover an unknown mangrove swamp on our island as our predecessors had!

Deliberately, an island that provided, relatively, easy access was selected.

And the final cautionary approach was, deliberately, we contracted a vastly experienced expert to lead the eradication. So the thirteen hectare Ile Vache Marine in Peros Banhos was selected.

Fast forward to two separate occasions prior to 2014. I was back on the island with Yanick, a Connect Chagos graduate. Together we conducted research on the number of land crabs present on the island to inform how much bait would be needed for the operation.

A year or so later I was back with Claudia, also a Connect Chagos graduate and now a CCT trustee. This time we were gathering baseline data to be used to assess the effect of removing rats, if the operation was successful. After we finished our work, together  we planted a tree, hoping that when the rats had gone it would flourish.

we planted a tree, hoping that when the rats had gone it would flourish.

I taught them both science, they taught me to appreciate the island.

In August 2014 all of the pieces of the jigsaw were in place. With irreplaceable assistance from the UK military contingent on Diego Garcia who had gone ahead of us and carried out some essential vegetation management on our behalf, we landed our equipment and stores.

Two weeks later our eradication mission completed, all we had to do was wait, for two years, to see if we had been successful.

Fast forward again, this time to April 2017. The same team of myself and Dr. Grant Harper from BioRestoration Ltd, New Zealand, were back on Ile Vache Marine to assess our work of two years previous and hopefully declare the island as the first successful rat eradication in the territory.

To say that the approach boat journey to the island produced butterflies was an understatement, more like frigatebirds! Secretly, I was confident. I had visited the island three times since the eradication operation and I knew the signs were good. However, I had to convince Grant our rat expert.

To say that the approach boat journey to the island produced butterflies was an understatement, more like frigatebirds! Secretly, I was confident. I had visited the island three times since the eradication operation and I knew the signs were good. However, I had to convince Grant our rat expert.

We started with a walk around the circumference of the island, a general look-see.

First impressions were favourable; some 30 pairs of Great-crested Terns were breeding and had eggs, small chicks and some large “runners”. A good sign but not a clincher.

Once the island had been circumnavigated it was time to delve into the interior. All the tracks that took the blood, sweat and tears of our military friends to complete had disappeared; we pushed our way in to the interior anyway.

Inside the forest had changed.

The floor of the forest was covered with sprouting shoots. Fallen fruit was germinating instead of being eaten by rats. Flowers were flowering. Grant was smiling. I was smiling too because I could hear above us the calling of Brown Noddy and White Tern chicks, a sound all but lost to the island in the days of rats.

I asked Grant if we could we say it was a success now? Not yet was the disappointing reply.

I asked Grant if we could we say it was a success now? Not yet was the disappointing reply.

We had to spend the night on the island and patrol with powerful lamps through the hours of darkness looking for the shine of rat eyes. It was a long, tiring and at times, a heart-stopping night. I never knew spider’s eyes could look so bright and large!

However, come morning, Grant was content the island was free of rats.

I sat on the beach as the sun came up and reflected on the eight years I had been involved with the project. From its conception following discussions with the then BIOT Science Advisor, CCT member Professor Charles Sheppard, as we walked around the rat-infested island. From baseline data gathering expeditions with experts from various disciplines such as CCT trustee Dr. Colin Clubbe and the Connect Chagos graduates. To the military personnel from Diego Garcia who as only the military can worked so stoically under such arduous conditions and never complained. And of course to Grant, a dedicated, professional super-fit expert in his field.

It made me think that hope does spring eternal and one day, trees such as the one we planted, in my mind a symbol of this project that pulled so many disparate organisations together in a unified cause, would be sprouting all over an archipelago free of an invasive predator introduced by man.

-----------------

In 2014 CCT conducted a rat eradication project, funded by the Darwin Initiative, as part of a long-term strategy to eradicate invasive rats from all of the Chagos Archipelago’s affected islands. It is internationally recognised that a minimum period of two years has to pass before an island can be declared rat free.

In 2014 CCT conducted a rat eradication project, funded by the Darwin Initiative, as part of a long-term strategy to eradicate invasive rats from all of the Chagos Archipelago’s affected islands. It is internationally recognised that a minimum period of two years has to pass before an island can be declared rat free.

The 2017 expedition was funded by CCT and joined a Bertarelli Foundation emergency expedition.

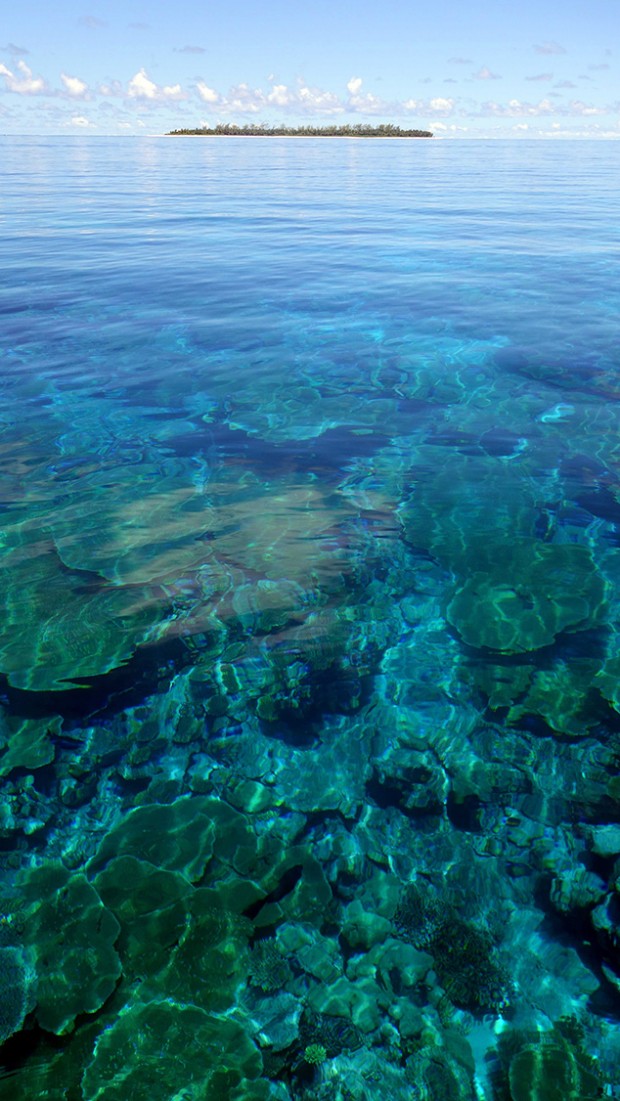

Photos: Pete Carr surveying (c) Grant Harper, Ile Vache Marine (c) Jon Slayer, Claudia planting (c) Pete Carr, Landing on Ile Vache Marine (c) Grant Harper, Grant preparing to survey (c) Pete Carr, Claudia and Pete's tree (c) Pete Carr