2015 Darwin Science Expedition - Day 18 Nelson Island and the Great Chagos Bank

Darks skies and ominous clouds threatened on the horizon as we prepared for the days dives. A blown fuse on the winch that carries our dive boats off the research vessel and into the sea delayed us and the clouds drew swiftly in and a torrent of tropical rain was on us before we could get started. Knowing the nature of the weather out here we decided to give it some time and sure enough we were off diving when the crane was fixed without rain belting round us.

Motoring around to the north side of Nelson Island we dropped the divers down and I was on top cover. Seabirds whirled over the island in their hundreds. Free of historical human disturbance this island is rich with several species and they were all out riding the windy tail of the squall. Several lesser noddy drifted over to examine me on my bobbing dive boat contemplating whether to land on the pontoons either side of me.

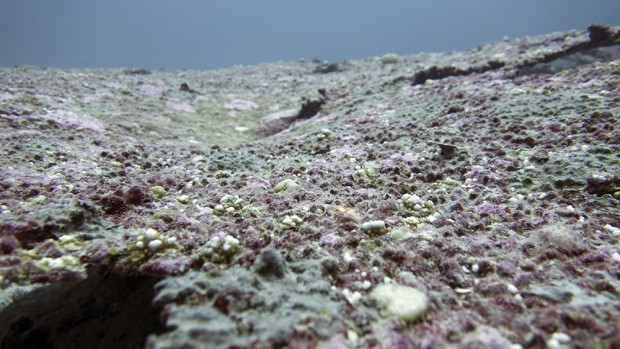

Beneath me the divers worked away with the only sign of their presence being the occasional eruption of bubbles breaking through the choppy waves. Their reports on returning to the surface were a contrast to the vibrant thriving life over the island. Here it seems the seabed comprised mostly of dead coral skeletons overgrown with algae. Something had killed them in the last year or two. Reassuringly though there were numerous tiny coral recruits, juvenile corals, establishing themselves amongst the algae on these dead skeletons. Ronan has been looking into this with his research and if you continue reading I've included his words after this short report on the days activities.

After a trip back to the research vessel for lunch the lagoonside dive in the early afternoon provided a possible explanation for the large area of dead coral on the opposite shore of the island. Where we dropped in to the lagoon there was a blend of sandy seabed and thickets of branching coral in the shallows. As we headed deeper this turned to a large area of dead coral and coral rubble. As we approached this dead area a crown of thorns starfish appeared. Further along in the dive another, and another. These coral predators are known to have population explosions in areas, for reasons as yet not fully understood, and it seems that perhaps there has been an outbreak here too killing off swathes of coral.

We certainly hope the reefs here are sufficiently healthy to rebound from a localized impact like this. Although there were dead patches there were also stands of diverse and healthy corals with the large numbers of fish that are characteristic of this MPA. On one of them I noticed an octopus camouflaged on a coral head beneath a shoal of silvery fish. As I approached it felt threatened by a sizable black grouper and ballooned its legs and body whilst changing colour in the blink of an eye to a stark white. The silvery fish exploded outward at this display and the grouper made a retreat. Evidence of the circle of life continuing despite an element of compromise from the crown of thorns.

VIDEO https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PYoCZl7uzj8

Done with the days diving we returned to the research vessel and began our navigation across to the next survey sites around the Three Brothers on the western edge of the Great Chagos Bank. All being well we’ll be there around midnight ready for tomorrows activities. Read on for Ronan's thoughts on the coral mortality we witnessed today.

A dark squall with wind and rain moving in has prevented launching of the dive boats this morning. The first bit of poor weather – we have been lucky so far on this year’s expedition. Hopefully it will pass quickly so that we can get to this morning’s dive site, which is on the seaward side of the island we are anchored off.

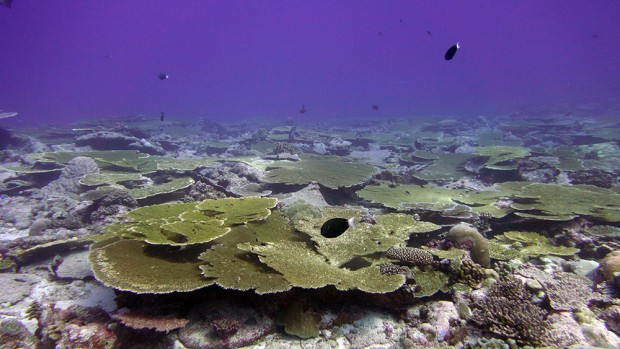

Many sites we have now visited during each of the last three years, others only once or twice since 2006. Change can happen rapidly on coral reefs, and we are building up an increasingly detailed picture of how the reefs of Chagos are changing. Most noticeable since 2006 is the mortality of the large colonies of table-shaped Acropora which can reach over 3 meters in diameter. The reasons for this change are not clear – it is possible be that these corals have simply reached the end of their life span, but bleaching due to high temperatures and disease may also play a part – both of which are being investigated during this year’s expedition.

The squall passes within an hour, and the dive boats are launched one by one from the stern of the research vessel, using the vessel’s A-frame, the whole process taking about a half an hour before all three boats are on the water and loaded with dive kit and research equipment. We work our way around the island to the more exposed seaward side and finally enter the water. It is a dramatic site; with a narrow reef terrace dropping rapidly down to a near vertical slope extending as far as the eye can see. At about 25 m deep where we start our work, the site has a similar appearance to many of the sites we have been diving over the last two weeks, with one major difference – the corals here are almost all dead.

Dead table Acropora cover most of the reef surface, and are overturned and tumbling down the reef slope. At the shallower depths, the coral returns to life somewhat, but the majority of the reef is dead. What is striking is how complete the mortality is – suggesting that the cause must have affected all colonies at the same time. We know that there was an outbreak of crown-of-thorns starfish observed feeding on the coral around this island observed in 2012, but it seems unlikely that this could be the only cause. The crown-of-thorns were mostly observed on the sheltered lagoon side of the island, so when we drop into the water on the afternoon’s dive, I am not expecting a flourishing reef. I am pleasantly surprised – although there are large patches of dead staghorn Acropora, there are also areas that appear not to have been affected.

Disturbances and coral death are part of the natural cycle of coral reefs – giving rise to the reef sediment which sustains the islands. The key is really not whether damage or coral die-offs occur, but how the reef recovers from them when they do. For me, one of the most encouraging signs this year is the abundance of young coral colonies, which on many sites are covering much of the available substrate of dead coral colonies. This is a key sign of reef recovery and ultimately a coral reef which is resilient to damage and disturbance. If these young recruits can continue to grow and contribute their full potential to reef development, the future of the coral reefs of Chagos looks very positive.