2015 Darwin Science Expedition - Day 13 - Ile Takamaka & Sam’s Knoll

VIDEO https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VqvFDI6tTWo

The day started with some tricky conditions for navigation in our small boats. A large rolling swell moving in from the south while the wind freshened from the North…so a northerly chop and a southerly swell. No lee-side to the atoll today so it was a bouncy ride in all directions. We started the day with a morning dive off Ile Takamaka where I accompanied Ronan and John as they conducted their video transects and data collection on the gentle reef slope off the south eastern corner of the atoll.

The dive also yielded up a lovely turtle encounter. Two turtle criss crossing right in front of my camera.

VIDEO https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GdEUy3862AA

For the afternoon we stuck to the lagoon to find shelter from the challenging Oceanside seas. Sam’s Knoll is just on the inside of Ile Anglaise and offered up the rich towering coral structures and gardens that are so typical of this very sheltered lagoon.

VIDEO https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AAUBRoH2nSw

Corals grow on corals grow on corals here with an impressive variety of form and hue. These in turn offer up a rich environment for fish – such as these Yellow Sweeper (Parapricanthus ransonneti) sheltering amongst the branches of a heliopora coral. On the top of this knoll the coral gardens are incredibly lush, an arrangement of richly varied corals towering toward the surface in a mad cluster of form and colour.

This evening I’ll be accompanying Pete as he heads ashore to Ile Mapou to carry out some Coconut Crab surveys…more to report on that tomorrow! A beautiful afternoon I’m sure it’ll be lovely on the island…I'll report on that tomorrow, for the moment I'll leave you with some words from Courtney on how her research and expedition is going.

When you hear the word “Chagos” what comes to your mind? Most people around the world have never heard of this far off place. Those that have instantly think about the politics surrounding the Chagosians. And then there is an even smaller subset of people that picture remote islands swarmed by seabirds, crystal clear water, diverse and healthy coral reefs and fish so abundant that it’s difficult to focus on anything else underwater.

Last year, I was fortunate enough to join the minority of people that have experienced how special Chagos’s unique ecosystems are. I left last year’s expedition profoundly humbled by Chagos, itching to continue my work on coral health, but just grateful for this “once in a lifetime” experience. Well, just 10 months later I was invited back to participate in the 2015 Darwin Expedition providing me with an invaluable opportunity to dig deeper into what’s driving the health of Chagos’s coral.

Much like going to the doctor’s office, assessing coral health and disease levels can provide an early warning of changing reef health that cannot be detected by just looking at the amount of coral on a particular reef. Although coral disease is a natural component of healthy ecosystems it can drastically reshape ecosystem structure and function.

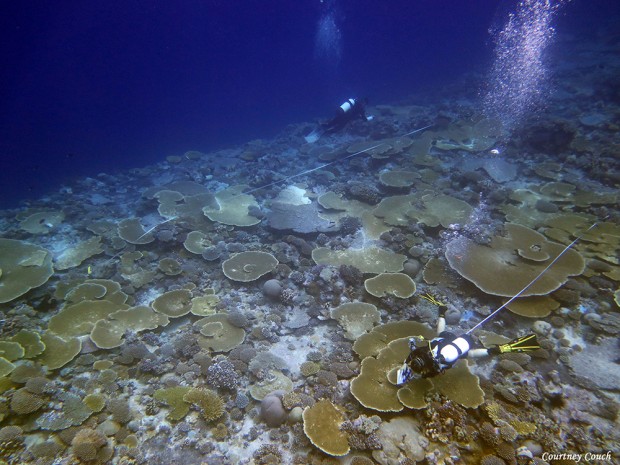

Last year I conducted the first comprehensive in situ coral disease assessment in Chagos and discovered relatively low disease overall compared to other reefs around the world. However, I was surprised to find that despite the low overall level of disease, white syndrome was locally high at some reefs. White syndrome is a disease that causes gradual mortality of corals and is targeting one of the region’s dominant reef building corals, the table corals. While this disease has been associated with bacterial infections in other Indo-Pacific regions, its causes in Chagos are still unclear.

In early March, I made the 60 hour transit from Hawaii to Chagos to answer an ambitious list of questions: Has disease level changed since 2014? Why are some reefs more or less susceptible to white syndrome than others? How quickly is this disease killing coral colonies and has this changed since last year? Are there specific pathogens associated with this disease? What happens to the colonies when they die - do they become a home for new coral recruits (coral babies)? Much like forest ecosystems affected by fires, I also wanted to know how quickly corals are recruiting back onto the reef and how this might affect reef recovery.

While our days varied widely from the epically calm conditions with dolphins playing in our bubbles to the more challenging 12’ swells and high current, my days generally followed the same routine. I have a strong aversion to being rushed in the mornings, so I generally woke up at 6:15 each day, made my way out to the back deck to set up my kit (aka dive gear for all my American friends reading this post) while the sun was just beginning to rise. After making sure my camera, GPS and other science accessories were sorted, I made my way up to the top deck for some yoga. By 8:00 we were “kitted up” on the back deck and ready to launch the small zodiacs. If all went according to plan, we were motoring out to our first site of the day by 8:30 and underwater shortly there after. My first goals underwater were to quantify the proportion of the coral population was affected by disease, what type of disease were present on that reef, which coral types were affected and how much recruitment there was. I did this by laying out several transect tapes across the reef. If time permitted, I also tagged colonies with disease to determine the fate of these colonies over time and identify which coral species are recruiting onto the dead substrate. On other dives, I also collected a small number of samples from healthy and diseased table corals, which I will be sending to my colleagues who study coral microbes to identify possible pathogens. After our morning dive we returned to ship ate lunch, kitted back up and headed out for the afternoon dive. Rinse and repeat.

While the presence of coral disease and the resulting mortality we are observing in a remote area like Chagos is concerning, it’s important that we focus on the unique lessons we can learn from this system. First, the fact that we are seeing isolated but high levels of disease in remote areas emphasizes the importance of improving our understanding of global stressors such as climate change and doing our best to reduce our carbon emissions no matter how far you are from coral reefs. Secondly, many of Chagos’s reefs are still incredibly healthy and we should focus on the why. It’s also important to remember that Chagos’s reefs have demonstrated an astounding capacity for recovery. These reefs recovered after just 15 years following the 1998 bleaching event and many reefs recently hit by disease are showing signs of strong coral recruitment. Large marine protected areas (MPAs), such as the British Indian Ocean Territory/Chagos Archipelago provide a unique opportunity to enhance coral reef resilience by minimizing stress and boosting recovery following disturbance events.

Lastly, I’ve learned that while it’s crucial to improve our understanding of marine ecosystems through science to enhance marine conservation. It’s equally important to let the rest of the world know that these spectacular ecosystems exist and are in dire need of protection.